The Role of Manufacturing and Coos County

Is manufacturing still important? This is a question often asked by people in both urban and rural communities. As an industry, manufacturing has always been a hub for job creation and the development of new technologies. We have seen the industry shift from an infancy where steam and water power supplanted hand-operated production, to the use of electricity and assembly lines. More recently, computerization has increased workplace efficiencies resulting in new products as well as changes in worker skill sets. Today, we have entered the Fourth Industrial Revolution where computerization is promoting the further implementation of smart technologies. The development of technology-enabled platforms is creating a work environment where interconnected machines, not workers, directly determine production decisions and processes. Manufacturing’s importance is more than its total employment level; it also includes overall community impact in terms of wages, skill sets, and ripple effects across the local economy.

Location Is a Cost Factor

Manufacturing depends on access to needed resources. Inputs include labor as well as raw materials such as timber for wood product manufacturing or computer components used in building products that are more advanced.

Economically obtaining input materials and distributing products depends on type and location of transportation networks, communications systems, proximity to suppliers, and nearness of suitable markets. Rural areas, once home to extensive sawmills and related plants, are finding themselves farther and farther away from needed materials and markets. Rural communities having ready access to rail and ships, especially important for transporting bulk materials, are more likely to attract and retain manufacturing businesses than those towns located in more isolated parts of the state.

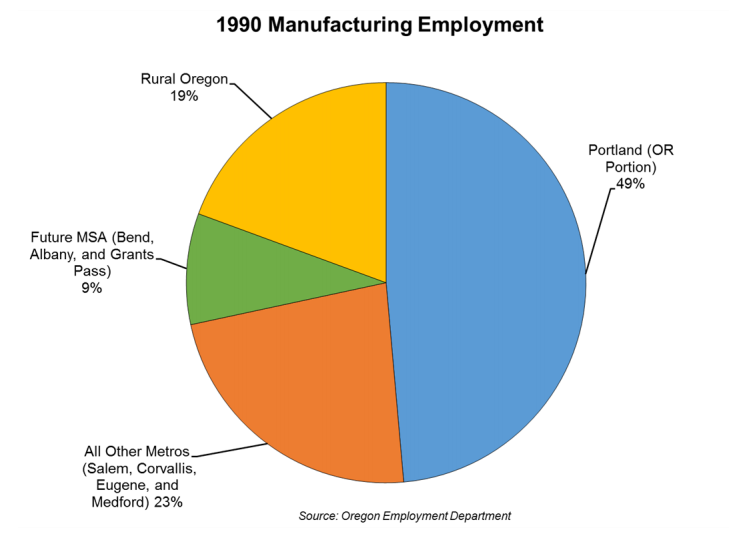

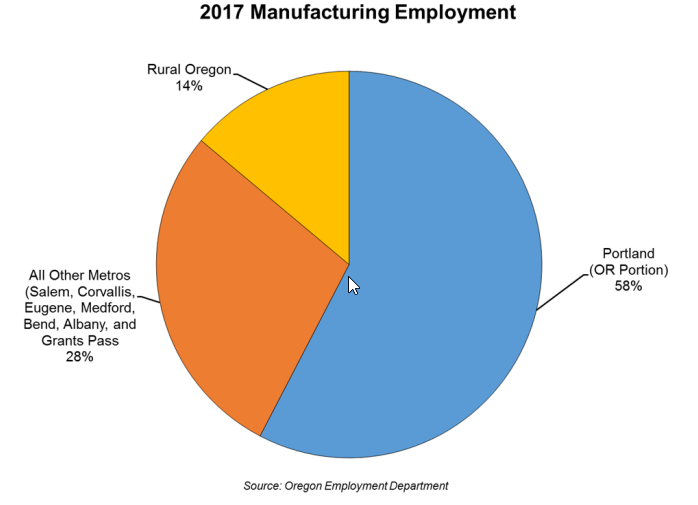

Oregon has seen a shift in manufacturing from rural areas to its urban centers. This reflects, in part, increased transportation systems, development of distribution centers, and clustering of similar and supportive businesses that provide a pool of workers with complementary and transferable skill sets. The synergy generated within a community of manufacturing operations ripples across the urban landscapes. In 1990, rural Oregon was home to nearly one out of five manufacturing jobs. By 2017, rural Oregon’s share had declined to 14 percent. In contrast, the Portland metropolitan area grew from providing manufacturing jobs to nearly half of the industry’s employment to 58 percent.

In addition to the shift in location, the employment footprint of manufacturing has changed. In 1990, the goods-producing sector accounted for nearly 18 percent of all payroll jobs. By 2001, it accounted for 14 percent; and by 2017, manufacturing employment provided only 10 percent of Oregon’s jobs. In contrast to an overall industry decline in employment, food manufacturing gained 7,600 jobs (+34.4%), and the beverages arena gained nearly 4,000 jobs. Food manufacturing includes frozen food manufacturing, bread and bakery products, fruit and vegetable canning, seafood product preparation and packaging, dairy products, etc. The beverage sector includes Oregon’s rapidly expanding wineries and breweries. All these products require efficient transportation networks to carry produce from fields to processing plants and finished products to local and worldwide markets.

As overall manufacturing employment has declined, Oregon’s wood product manufacturing, a traditional mainstay of many rural communities, has been hit hard. In less than twenty years, this sector dropped more than 10,000 jobs (-31.2%, 2001-2017). In addition to the costs of siting and building mills and processing plants, natural resource-based manufacturing requires expansive transportation networks capable of handling often-bulky input materials. Whether products are shipped directly to consumers or to other industrial sites, transportation to and from Oregon’s rural communities tends to be far from resources and markets.

The transportation networks moving raw materials and processed materials from rural sites to consumers are not the only costs associated with location. Distance from populated, urban centers also affects labor costs. Although rural manufacturing is keeping pace with urban industrial trends, such as increasing automation and reliance on sophisticated technological changes, recruiting and retaining workers with appropriate skills sets adds to the expense of doing business.

Manufacturing in Rural Coos County Differs from Oregon

In 2001, Coos County manufacturing accounted for 8 percent of the county’s employment base. Although the percentage of employment dropped to roughly 7 percent during the recession, today, it still accounts for 8 percent of the county’s employment. Within this sector, two arenas traditionally have dominated the scene. Twenty years ago, wood product manufacturing made up 48 percent of county manufacturing employment, and food manufacturing accounted for 20 percent of the sector employment. By 2018, wood product manufacturing generated 52 percent of overall manufacturing employment. Within this subsector, veneer and engineered wood product manufacturing increased its employment levels. Food manufacturing held relatively steady at 18 percent. In contrast to other manufacturing subsectors, food manufacturing is one of a very few sectors across the county’s economy that has continued to offer relatively stable employment levels before, during, and after the recession.

The employment percentages of the manufacturing sector mask an underlying loss of jobs. True, manufacturing appears to be holding its own. In reality, not only does Coos County’s total nonfarm employment remain 4 percent below pre-recession peak levels (-980 jobs), manufacturing is about 110 jobs below peak. In welcome contrast, wood product manufacturing has recovered its former employment level (+100). As new products such as cross-laminated timber (CLT) and mass plywood panels (MPP) make their way into the marketplace, rural wood product manufacturing is positioned to take advantage of these new technologies and markets.

In contrast to Coos County’s total nonfarm employment and its manufacturing sector, Oregon’s total nonfarm employment is now more than 10 percent above the prior peak. Manufacturing is 6 percent below, and the state’s wood product manufacturing employment is more than 28 percent below its high point in 2005.

Importance in Jobs, Wages, and Benefits

Manufacturing’s importance is more than the employment it provides. Even as the industry’s employment steadily declines, reflecting increased automation and technological advances, the wages are higher than those paid in other industry sectors. Oregon’s annual average wage (2017) is $51,117. Statewide, manufacturing wages average $68,152. This ranges from $131,053 in computer and electronic manufacturing (not typically located in rural areas) to $42,828 in food manufacturing and $49,430 in wood product manufacturing.

Coos County’s overall average annual wage is $38,032. Manufacturing wages average $47,940. Food manufacturing, which has historically paid less than other sectors, averages $24,336. Wood product manufacturing, accounting for roughly half of county manufacturing jobs, averages $50,587. Based on wages, for every one manufacturing job, there are 1.3 all-industry jobs; 1.7 retail jobs; and 2.4 leisure and hospitality jobs. Wages tend to vary with workers’ education and skills; their ability to critically evaluate processes and make sound decisions; use of technology; and the business’s ease in recruiting and retaining qualified employees. As such, average annual wages are a rough proxy for education or skill requirements.

Not only do these higher-than-average manufacturing wages affect the area, job-associated benefits provide additional value. A recent benefits survey by the Oregon Employment Department found that 69 percent of Oregon’s manufacturing employers provided health benefits to full-time employees; 58 percent offered health benefits to full-time employees’ dependents. Fifty-seven percent provided dental benefits to full-time workers, and 50 percent provided vision insurance. Sixty percent of manufacturing employers offered retirement benefits to full-time employees, and 20 percent offered those benefits to part-time workers. Additionally, manufacturing employers provided 70 percent of full-time workers with paid holidays; 58 percent with annual pay raises; and 58 percent with paid vacation. Research shows that an employer’s ability to offer benefits is not only a recruitment tool but affects employee retention – all contributing to the overall economic stability of the workforce and the community.

Looking Ahead – Manufacturing Processes, Skills, and New Products

As the Fourth Industrial Revolution changes today’s economic landscape, manufacturing’s capacity to lead technological innovations will continue to propel the industry from its roots as a processdriven sector to a knowledge-based one. The ripple effects, quantified as multipliers, measure how changes in one industry cascade across the rest of the economy. Although specific to a given region and industry, manufacturing not only has a higher multiplier effect than service industries in the same region, it has the highest multiplier effect of all sectors. Broadly speaking, every dollar spent in manufacturing adds at least $1.89 to the economy; every one manufacturing employee results in the addition of nearly four employees elsewhere in the area (National Association of Manufacturers).

Rural Coos County’s focus on natural resourcebased manufacturing will continue to be influenced by its location. Being several hours drive from Interstate 5 complicates reliance on truck transport. However, easy access to the International Port of Coos Bay, a major deep draft coastal harbor, facilitates movement of such bulk cargo as raw logs and wood chips. The industry’s need for reliable, efficient transportation networks; high-speed communication systems; and successful recruitment and retention of qualified workers will also be affected by public environmental policies and regulations. Manufacturing’s innovation, use of new technologies, development of new products, and influence on economic systems offer the manufacturing sector unparalleled opportunities in the days ahead.

Annette Shelton-Tiderman

Regional Economist Coos, Curry, and Douglas counties

annette.i.shelton-tiderman@oregon.gov

990 S 2nd Street Coos Bay, OR 97420

Annette Shelton-Tiderman was born and raised in Moscow, Idaho, and attended the University of Idaho (BS, MS, JD). She spent many hours of her childhood “helping” in the family bookstore where she developed a long-lasting appreciation of small business and community focus. After graduation from the University College of Law, Annette moved to Oregon where she focused on economic-related research and writing. She went to work for the Oregon Employment Department as the Salem Area Workforce Analyst (1999) – a job that eventually took her to eastern Oregon and then to southwestern Oregon. Annette has been southwestern Oregon’s Regional Economist since 2016. She has recently retired from state service (May 2019).

Advertisement