Oregon’s Child Care Industry

Social and economic trends over the past 60 years have made child care a workforce issue and turned child care into an industry. The share of women participating in the labor force nearly doubled between 1950 and 2000, before reaching a plateau in recent years. Labor force participation rates are higher among parents than among those without children under the age of 18. Among parents of young children under the age of six, nine out of 10 fathers and six out of 10 mothers are working. Today, most parents are in the labor force and employed, translating into a lot of children needing child care.

Parents make up a sizeable share of Oregon’s labor force. Parents of children under six years of age make up 14 percent of Oregon’s workforce, and those with children ages six to 17 make up another 18 percent. Oregon employers benefit from the services of child care providers because these services help their workforce continue to be stable, reliable, and productive.

Parents of children under six years of age make up 14 percent of Oregon’s workforce

So, how big is the child care industry in Oregon, and has it kept pace with the demand for paid care?

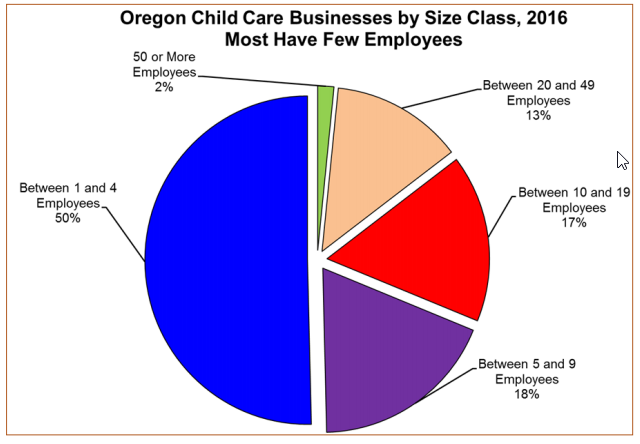

The Industry In 2016, Oregon’s private-sector child care businesses numbered 1,187 and employed 11,421 workers. Half of the businesses had four or fewer employees. Fifteen percent of child care businesses employ 20 or more workers.

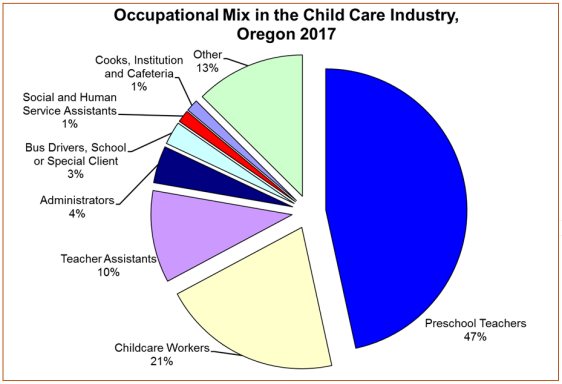

Wages are low in the industry, an issue that is often linked with quality of care. Total payroll of child care businesses with employees in 2016 was about $262 million – this averages out to an annual industry wage of $23,000, less than half the all-industry average of $47,700 (as shown in the Census Bureau’s County Business Patterns data set). One reason for a low average wage could be the low wages of the occupations that dominate the industry. For example, the median wage of a preschool teacher in Oregon in 2018 is $13.91 per hour, and the median wage for childcare workers is $11.98. These two occupations account for more than two-thirds of the employment in the day care industry.

Employment in child day care businesses with employees grew 33 percent from 2007 to 2017 – a bit faster than the 30 percent growth rate in the larger industry sector of health care and social assistance. All-industry employment grew just 9 percent from 2007 to 2017.

Is the Supply of Quality Child Care Adequate?

Child care and early education is important to today’s workforce – in that it allows parents to be present at work. It is important to tomorrow’s workforce as quality child care gives the next generation a solid start in their education. There is some evidence that points to a shortage of available day care services. According to the most recent report from the Oregon Child Care Research Partnership (Child Care and Education in Oregon and Its Counties: 2014), the supply of child care spots was 17 per 100 children under 13 years old. In order to meet demand, 25 spots per hundred children were needed. This shortage was particularly acute for children with special needs, infants and toddlers, and evening care for children of parents who work late shifts.

Additional research from the Oregon Child Care Research Partnership (Oregon Early Learning Workforce), shows that turnover among regulated child care facilities far exceeds turnover at K-12 schools. In fact, between 2012 and 2016, the annual turnover rates in child care facilities ranged from 16 to 29 percent per year. In all, just 36 percent of the 2012 child care workforce were still working in child care in 2016. Programs paying lower wages tended to have lower levels of teacher retention than the industry norm.

The child care industry has grown in response to the increasing numbers of families in which both parents work, and to the increasing number of households headed by women. Supply of day care currently is not meeting potential demand.

As the importance of early childhood education is embraced and more fully supported, efforts are underway to better measure and support the professional development of child care workers and preschool teachers and more fully align their training and compensation with the broader array of educators. The study concluded, “Low wages are associated with high turnover rates in both early learning and K-12. High turnover rates harm children and challenge professional development investments; although in Oregon’s early learning workforce we find that those in whom we made professional development investments were mainly in the group who remained in the workforce.”

The child care industry has grown in response to the increasing numbers of families in which both parents work, and to the increasing number of households headed by women. Supply of day care currently is not meeting potential demand. Improved support of child care workers through professional development and retention strategies can improve both the availability and the quality of child care.

Jessica Nelson

Employment Economist

jessica.r.nelson@oregon.gov

875 Union St NE Salem, OR 97311

Advertisement