Why Oregon’s Labor Market is Tighter Than You Think

By Josh Lehner Oregon Office of Economic Analysis oregoneconomicanalysis.com

During recessions and the early stages of recoveries, hiring employers typically have more workers to choose from when it comes to filling job openings. Unemployed workers greatly outnumber job vacancies. When workers are competing with one another to a greater degree to get a job, it can hold down wage growth. Once the labor market tightens, employers generally need to compete more by increasing wages or other perks to attract and retain workers.

The pandemic recession is different. These usual dynamics are either accelerated or gone. Labor demand and wage growth remain strong, while the pool of candidates is smaller than you might think.

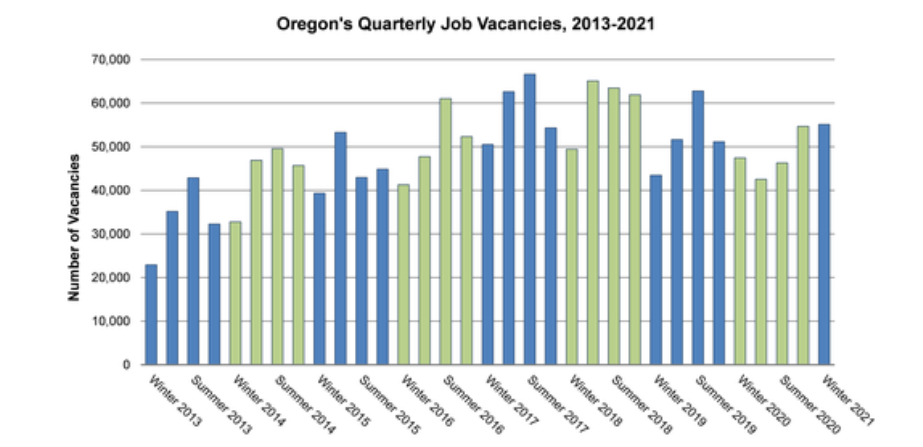

Nationally and here in Oregon job openings have returned to pre-pandemic levels. Businesses are advertising just as many vacancies today as back in the strong economy a couple years ago. Additionally, research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta shows that underlying wage growth remains in-line with pre-COVID trends as well. This combination indicates businesses are not responding to the pandemic recession as if there is a surplus of available workers. In fact a majority of Oregon employers (54%) are citing difficulty hiring workers, just as they have in recent years.

This recovery looks different because several simultaneous factors are constraining the supply of labor for job openings. These include a reduced or altered labor force due to COVID-related issues, transfer payments and benefits supporting households more during the pandemic, and rapid hiring during the re-opening period creating more intense competition among employers for workers.

Participation Issues

Pandemic Concerns

The unemployment rate doesn’t include would-be workers who are out of the labor force, meaning they neither have a job, nor are they looking for one. Supplemental information from households in the Current Population Survey shows an estimated 45,000 people in Oregon said they were prevented from looking for work due to COVID-related reasons during the first quarter of 2021. While vaccinations have accelerated, only about half the adult population has received at least one vaccine dose for COVID-19 as of mid-April. COVID case counts are also rising in many areas again this spring.

Lack of In-Person Schooling

The pandemic has also caused other labor market hurdles for workers, and parents in particular. Heading into the pandemic, one out of every six Oregonians in the labor force had kids, worked in an occupation that cannot be done remotely, and also did not have another non-working adult present in the household, according to research from the Office of Economic Analysis. Currently, three-fourths of Oregon’s K-12 schools have students learning remotely from home either part- or full-time, according to Oregon Department of Education records.

Even with the anticipated return of full-time, in-person learning for the 2021-2022 school year, child care slots, which were already too scarce in most areas of the state prior to the pandemic, and summer programs will likely continue operating with reduced capacity for some time. These constraints limit workforce options for some parents of younger children.

Federal Aid and Unemployment Benefits

Federal Support to Households

Fiscal stimulus and enhanced unemployment benefits during recessions has generally aimed to encourage economic demand, and support families during times of economic distress. These safety nets kicked in and seem to have accomplished those goals as the pandemic shut down large portions of the economy and governments asked people to stay home for public health and safety. Federal policy was explicitly designed to aid households and workers due to COVID.

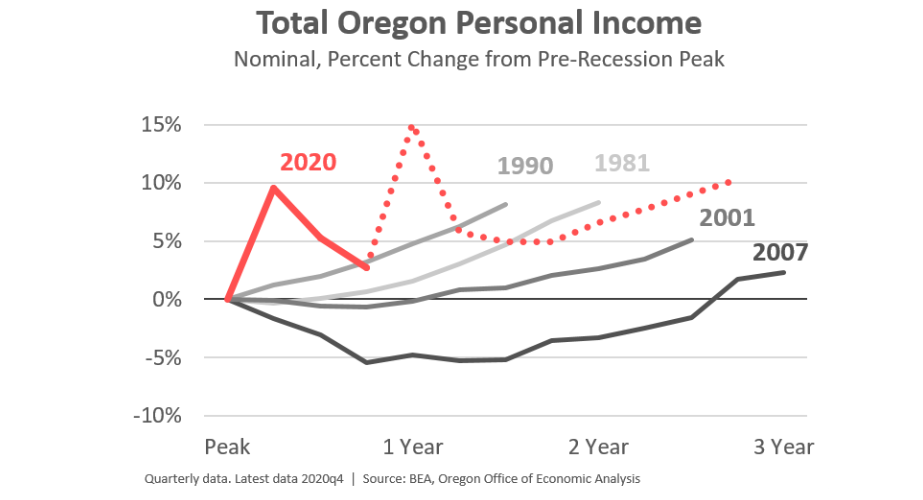

Total personal income in Oregon today is about 15% higher than before the pandemic. The primary reason is the strong federal fiscal policy response to the pandemic. The recovery rebates and enhanced unemployment insurance benefits each have added $12 billion to personal income in Oregon. This income support is the primary reason why the recovery and overall economic outlook is so bright. Even so, a stronger safety net where incomes are higher today than pre-COVID can reduce labor force participation in the short term for some workers. To the extent this is happening today, it is temporary.

Enhanced Unemployment

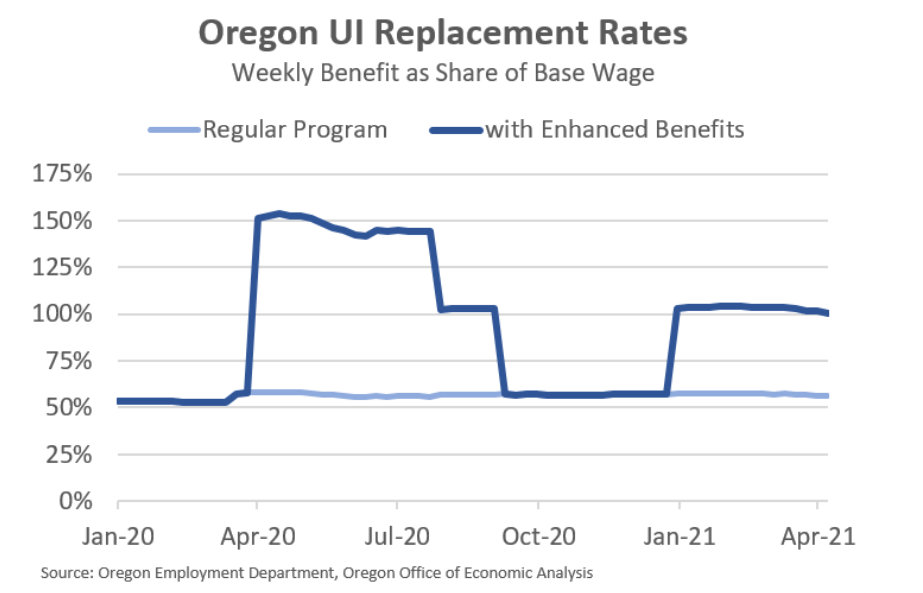

Federal Pandemic Unemployment

Compensation (FPUC) adds $300 onto weekly unemployment insurance benefits through September 4, 2021. In the first quarter of 2021, the weekly regular unemployment (UI) benefit has averaged $370 per week. With the additional $300 FPUC payment, that adds up to an average payment of $670 per week.

That’s roughly the same as earning $16.75 per hour for someone working full time. During the first quarter of 2021, that has also represented full wage replacement (between 100% and 104%) relative to regular UI claimants’ pre-pandemic earnings on the jobs. Some perspective here: earning $670 per week, working year round would total $34,800 in gross earnings for a worker. By comparison, the median earnings for full-time workers in Oregon in 2019 was $50,712. With “Now Hiring” signs in many business windows and stronger wage offerings as employers compete for available workers, it’s unlikely that this benefit, in itself, is keeping a vast number of workers on the sidelines.

Furthermore, unemployed workers cannot refuse job offers or a recall to their previous job (if temporarily laid off) because of their unemployment benefit amount. Refusing work solely due to weekly unemployment benefit payments would be considered fraud. The Employment Department provides ways to report job refusals.

Expanded Benefits Eligibility

Federal legislation passed in 2020 and 2021 created and has continued the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program. This provides unemployment benefits for the first time to self-employed, contract, and other workers not covered by UI if they lost work through no fault of their own. For eligible workers, PUA pays a minimum of $205 per week, and each eligible week of benefits will also include the additional $300 FPUC payment.

Prior to the pandemic recession, self-employed, freelance, or other workers whose employer was not subject to UI taxes would have no unemployment benefits available to them if they lost work. Presumably if their work or gigs dried up, some would look for and take a payroll job. The safety net provided by PUA benefits allows them to be supported and resume their self-employed or contract work once it’s possible and demand picks up again.

Concentrated Nature of the Shock

The pandemic recession and labor force dynamics differ significantly from both the dotcom bust and the Great Recession. Today’s economic pain is not evenly felt across the economy either.

Last spring, many businesses with similar labor pools shut down overnight. The economy experienced record-setting job losses and the unemployment rate increased nearly 10 percentage points in April 2020 alone. The pandemic recession unemployment has been overwhelmingly due to temporary layoff. Many unemployed Oregonians today indicate they are expecting to be recalled to their jobs when the time comes.

In the previous recessions, the job losses were largely permanent, and the economic nadir did not occur until more than two years into each cycle. As such, employers, at least those looking to hire at the time, saw excess labor supply accumulate over the course of years. Today, the changes occurred all at once. This includes reopening on a similar timeframe as well. Rather than protracted, increasing unemployment, the jobless numbers have dropped much faster during this recovery.

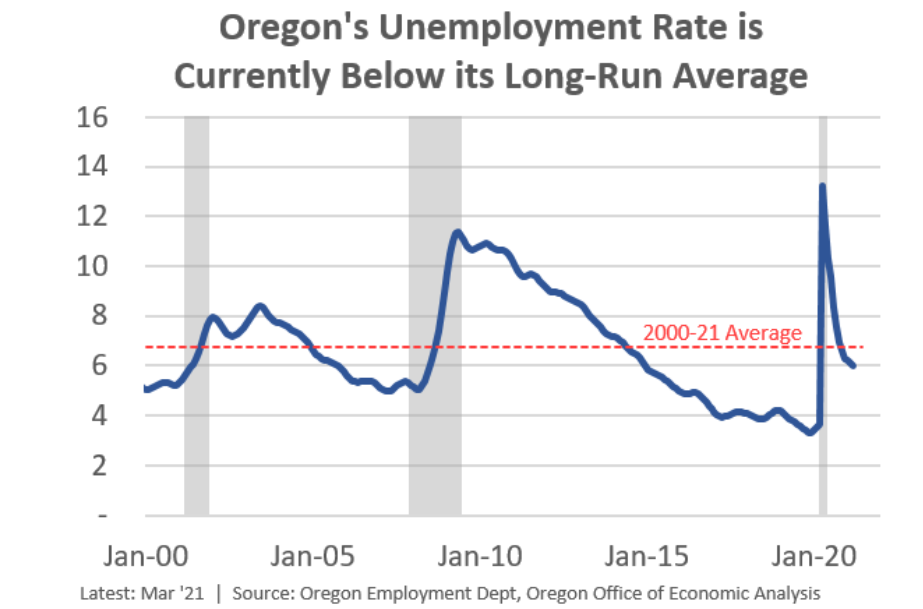

Oregon’s unemployment rate matched the nation’s at 6.0% in March, below the average of 6.8% over the past two decades. Currently, hiring employers are facing a typical or slightly lower-than-typical available labor pool for their job openings.

The available labor force is not evenly distributed either. While all sectors lost jobs in the initial COVID downturn, some have bounced back rapidly or hit new employment highs (such as transportation, warehousing and utilities, and professional and technical services). Depending upon the types of jobs employers are hiring for, there may be no excess labor. Some industries and firms face the same strong economy – growing revenues and increased staffing needs – today as they did pre-COVID, or at least the pandemic did not change their situation too terribly much.

Even within the high-contact, in-person service industries that have borne the brunt of the recession, the effective labor pool may be smaller than it looks. More than 60% of Oregon’s lost jobs in the spring of 2020 were in bars, hotels, nail salons, restaurants, and schools. Recent, large rebounds have been notable in leisure and hospitality, which has been adding more jobs per month than the overall economy did pre-COVID. As these businesses look to hire workers with similar skills at the same time, it does increase difficulty – and wages or perks – to get workers in the door and on the job.

Outlook

All told the labor market is tighter than we might expect so quickly after a deep shock to the economy. We expect the pandemic-specific challenges and issues related to COVID fear and lack of in-person school to ease this fall. Enhanced safety net supports will also expire.

A key question is what happens between now and then. At some point, declining COVID-related frictions, competition to hire workers, and relatively low unemployment will push to a market clearing wage that pulls more people back into the labor force. Will that make inflationary concerns come to pass as firms look to raise prices due to wages and other cost increases? Or will future dynamics play out more slowly than the dramatic spikes and drops in unemployment and monthly jobs gains seen over the past year?

As the pandemic wanes, and the economy returns to health, we expect the labor market to tighten further. The pool of available candidates will remain below-average even as sidelined workers come back into the labor force, and migration flows return. Employers will need to continue to cast a wider net, and dig deeper in their resume stack to attract and retain workers, just as they were doing pre-pandemic.

Advertisement