Who Can’t Work From Home During a Global Pandemic?

by Brandon Schrader

Workforce Analyst

OREGON EMPLOYMENT DEPARTMENT

COVID-19 rapidly spread across the United States and forced a patchwork of shutdowns that reduced business activity in order to save lives. Oregon is no exception as the “Stay Home, Save Lives” executive order was put into effect on March 23rd which enforced social distancing rules. While essential workers continued to brave the frontlines and millions of Americans were newly unemployed, a large portion of Oregon’s labor force has been working from home. The flexibility to work from home transformed from a highly sought-after benefit for employees to a coping mechanism for businesses to weather COVID-19.

While factors like government action and suppressed consumer spending habits also impact employment, telework has helped insulate a few industries from the effects of COVID-19. Sectors like information or finance don’t require much specialized equipment, industrial capital, or in-person experiences. As such, employees are able to continue helping customers. On the other hand, an industry like automotive manufacturing requires special equipment to build a car that can’t be taken home.

Access to telework and its benefits are far from equally distributed. Remote work is heavily stratified by industry and geographic area. To a degree, the root of access discrepancies are occupational type and educational attainment. However, much like the health effects of COVID-19, data suggests that marginalized groups like low-wage earners, individuals with less education, and Black communities have the least opportunity to telecommute. Understanding what demographics couldn’t work from home may offer some insight into who COVID-19 has disproportionality impacted and what sectors should be bracing for a possible second wave.

Adapting to COVID-19: What Tasks Can Be Done From Home?

Faced with few options, organizations who could shift to remote work did as a means to survive COVID-19. While only 8 percent of the American workforce telecommuted prior to the outbreak, more than half of workers were working from home in mid-May. Businesses that offered remote work may have been better positioned to adapt with social distancing policy. The ability to work from home stems from company culture, a job’s primary functions, and how customers receive goods or services. While workplace culture is malleable, especially under extenuating circumstances like a global pandemic, shifting the primary function of a job and service delivery is challenging.

To get a sense of whether or not a job could feasibly be done at home, a study from the University of Chicago examined “work context and generalized work activities” from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). The surveys asked if there was frequent contact with customers, in-person experiences, or specialized equipment. Each of these factors limit an employee’s ability to work remotely. Jobs were given a ranking based on responses which helped determine if none, part, or all of a position could be done at home. According to the study, 37 percent of occupations in the United States could realistically be done from home.

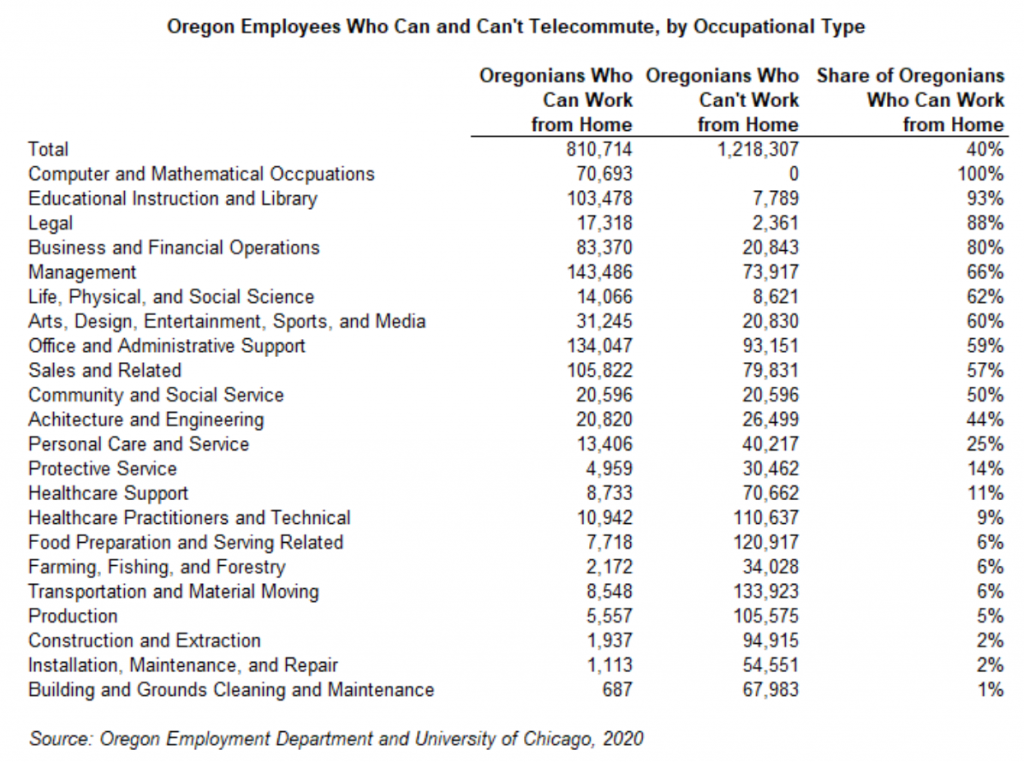

Vast Gaps in Remote Work Between Occupations

Cities are sometimes defined by their business community: San Francisco and Silicon Valley or New York and Wall Street are great examples. A little closer to home and you have “Silicon Forest” in the Beaverton-Hillsboro area. Breaking this down further, businesses are made up of different shares of occupations. Someone would expect a high number of computer-related jobs in an information-focused business like Apple or Google. If we assume the national estimates on the share of workers who can telecommute roughly approximate Oregon, we can learn about our workforce and who can (and can’t) telecommute.

While 100 percent of employees in computer and mathematical occupations were able to work from home only 1 percent of those in building and grounds cleaning and maintenance could telework. From another perspective, there are more employees in computer and mathematical occupations who can work from home than the bottom 11 industries combined. Over half of all the workers in Oregon who could potentially telecommute are in the five occupation groups with the best access to telework: computer and mathematical; educational instruction and library; legal; business and financial operations; and management. The presence of these occupations in different places and industries begins to tell a story of who can and can’t work from home.

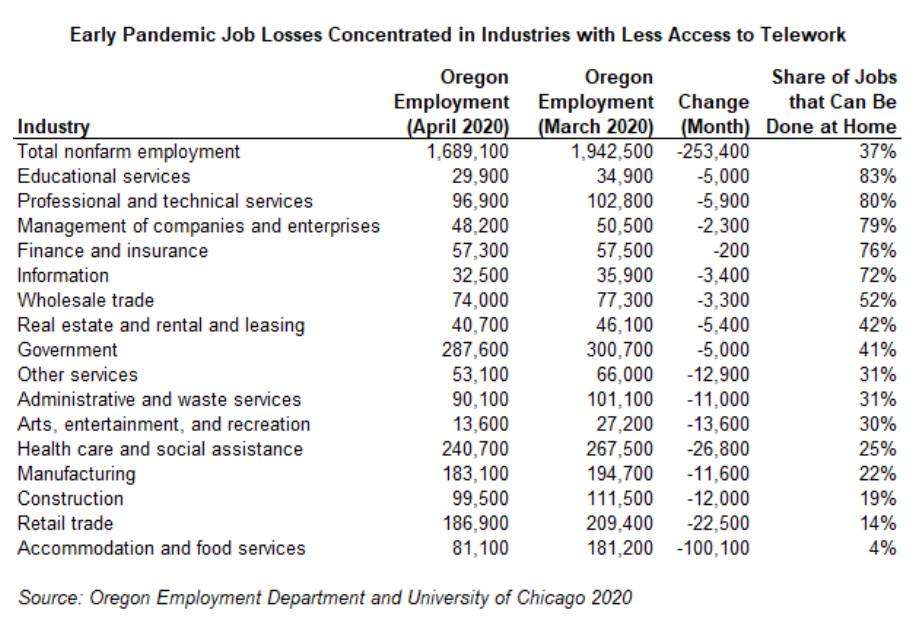

Industries with the Least Telework Access Faced Steep Job Losses

The building blocks of a business and an industry are the occupations within it. Unsurprisingly then, wide gaps in telework exist between sectors. For instance, while 83 percent of jobs in educational services could feasibly be done from home, just 4 percent of positions in accommodation and food services had access to remote work. A gap of almost 70 percentage points. To put this in perspective, accommodation and food services employed five times as many Oregonians as educational services prior to social distancing efforts. Yet, about 29,000 education jobs could potentially be done at home compared with only 7,200 in accommodation and food services. Unsurprisingly, accommodation and food services accounted for 40 percent of job losses between March and April 2020. Again, teachers and other public employees may face cuts in the future, but it still suggests that remote work may have staved off some initial declines.

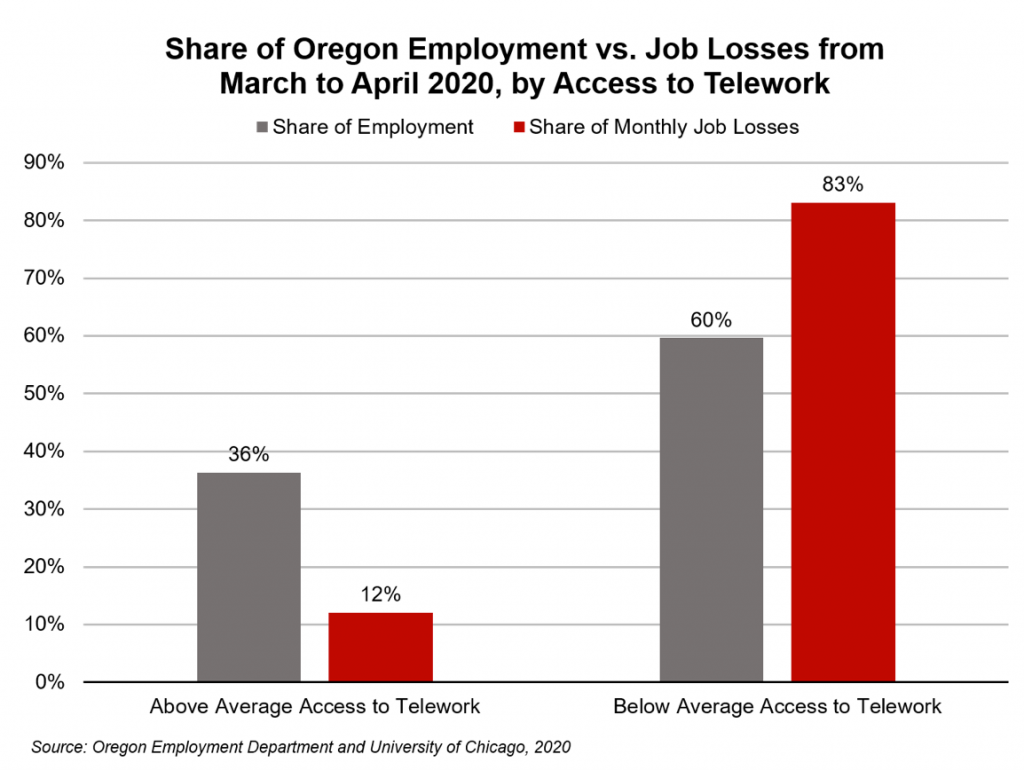

Industries split evenly around the national average of jobs with potential access to remote work at 37 percent – eight above and eight below. The quarter of a million jobs lost from March to April 2020 is a different story. Job losses were highly concentrated in sectors with below average access to telework options. Those sectors with less access to telework accounted for 60 percent of the pre-COVID-19 workforce, yet they made up 83 percent of job losses between March and April 2020. Conversely, industries with above average telecommuting access were vastly underrepresented in initial job losses. While those sectors made up 36 percent of the state’s employment in March 2020, they only made up 12 percent of monthly job losses.

Oregon Metro Areas Vary Greatly in Telework Access

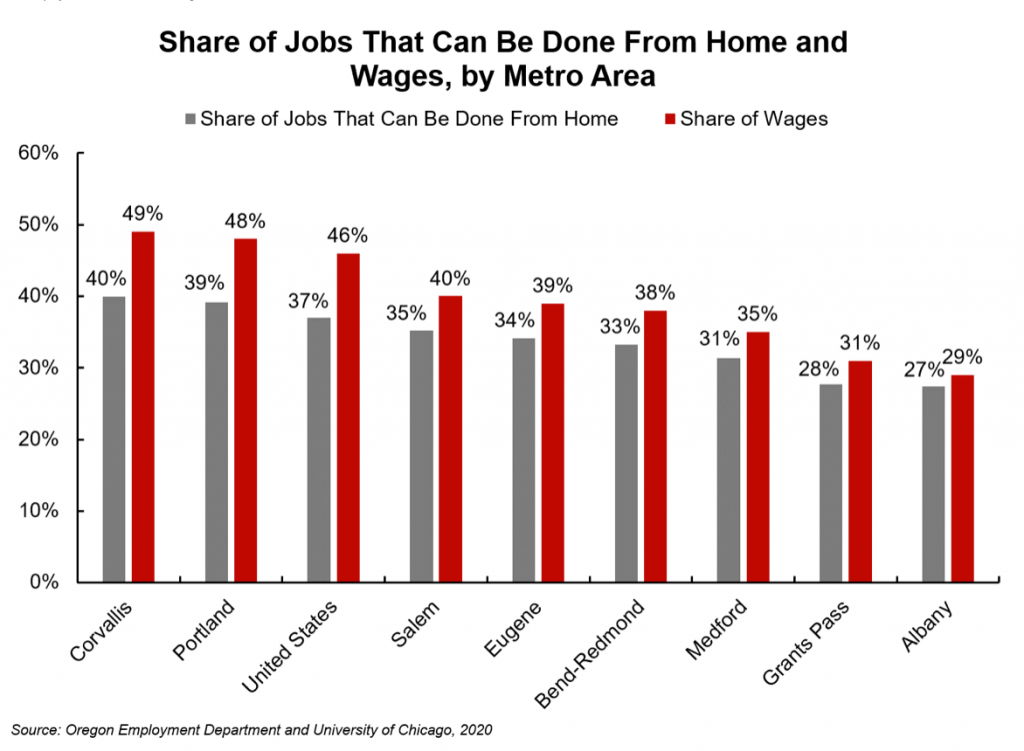

The composition of local businesses has major ramifications on the share of individuals who can work from home which results in a split amongst U.S. cities. Places like San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA (part of Silicon Valley) had the largest share of employees who could telework at 51 percent followed closely by Washington D.C. at 50 percent. Both metro areas have high concentrations of information and finance sectors. Las Vegas, NV and Fort Meyers, FL are common tourist destinations and tied for the smallest share of jobs that could be done at home with less than 25 percent. These are sobering figures. At best, half of workers still can’t realistically do their job from home.

Oregon follows a similar pattern. Corvallis MSA led the pack with 40 percent of jobs that could viably be done from home followed closely by Portland at 39 percent. Only 27 percent of jobs in Albany were telework compatible. The divide between industries can help explain why these gaps exist. These local business communities are fairly different. Both Portland and Corvallis have robust finance, information, and professional service industries which have some of the best remote work potential. Some of Albany’s most prominent sectors are manufacturing and retail trade, neither of which have more than 25 percent of jobs with telework access.

Across the board, Oregonians who could telecommute took home a larger share of wages than those who couldn’t. In Portland, 39 percent of jobs could be done from home yet they brought in 48 percent of all wages. Differences in the share of employment and wages were wider in areas with higher telework compatibility. As access to remote work declined, the gap between share of employees who could telework and share of wages also decreased. Most of Oregon’s metro areas had a smaller difference between the share of employment and wages compared with the United States average of 9 percentage points. In the U.S., 37 percent of jobs could be done from home while they accounted for 46 percent of wages. Regardless, high earners tend to have better remote work options, leaving low-wage workers vulnerable to financial loss.

Access to Telework Options Divided by Education and Race

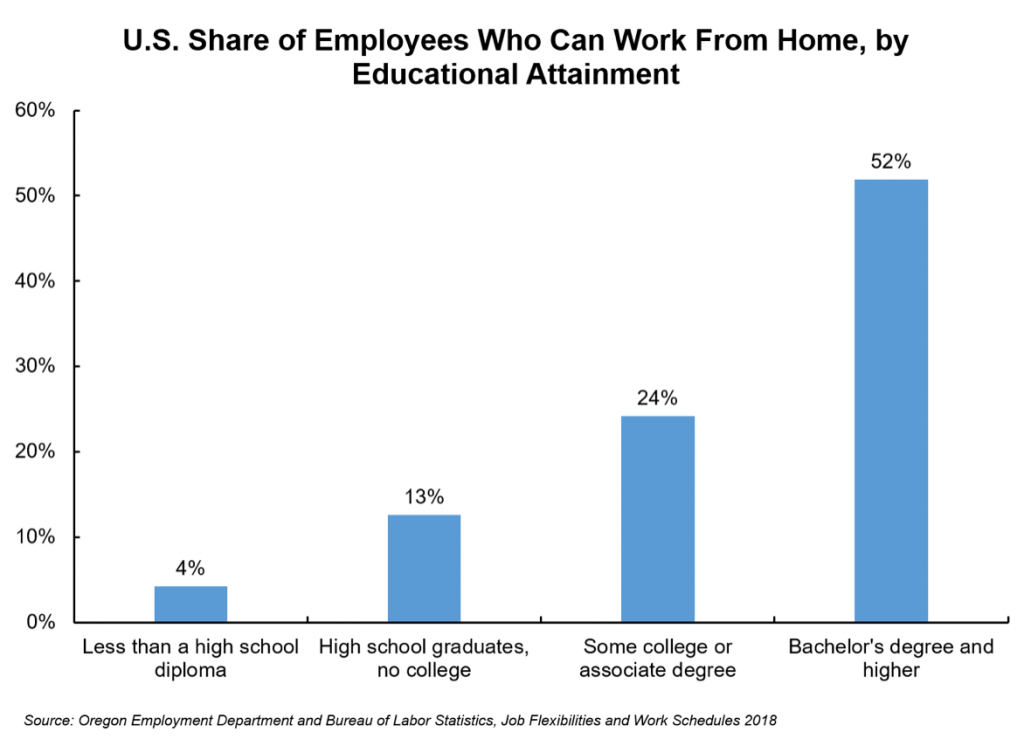

A pre-COVID-19 survey from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics examined who had the option to work from home by several demographics. Divides fell sharply along education and racial lines. A far greater number of Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree or higher had the option to work from home than any other education category. White Americans had far more remote work flexibility than Black and Hispanic or Latino communities. For education, 52 percent of employees with a bachelor’s degree or higher were able to work from home whereas only 4 percent of those with no high school diploma could telecommute. Even those who had an associate’s degree or some college had poor access to remote work – less than a quarter of workers could telework.

Assuming these national figures roughly reflect Oregon, only 204,000 workers without a bachelor’s degree had the option to work remotely, despite these workers making up 62 percent of the labor force. Worse yet, three out of four of those workers had at least some college or an associate’s degree. However, the number of Oregonians with a four-year degree or higher and access to telecommuting options towered over the combined total of all other education categories. More than 365,000 Oregonians with a bachelor’s degree or higher likely had access to work from home, yet the group only accounts for 38 percent of employment.

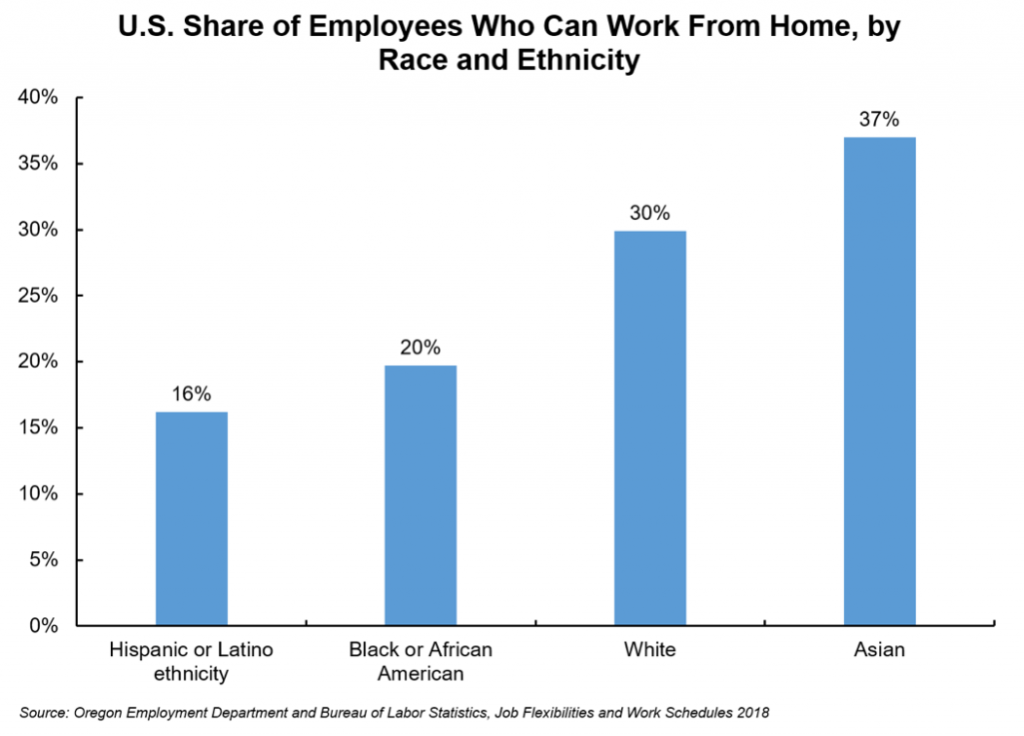

The racial gaps in access to telework are troubling. Asian Americans had the best telecommuting options with 37 percent of respondents saying they could work from home. After that, about 30 percent of white Americans reported having the option to work from home which is slightly above the national average of 28 percent. A steep drop occurs for both Black and Hispanic or Latino communities. By far, these groups of people had the least access to telecommuting options. Just over 16 percent of Hispanic and Latino individuals said they could work remotely; Black individuals had slightly better access at 19 percent.

A lack of telework options in the midst of a global pandemic is incredibly unfair and harmful, but is unfortunately unsurprising. Black and Hispanic workers make up about 30 percent of our national labor force, but are underrepresented in industries with the best access to telecommuting. Finance, education, and information sectors all have far less than 30 percent of their workforce made up of Black and Hispanic workers. Further exacerbating this trend, Black and Hispanic workers are overrepresented in some of the hardest hit industries like accommodation and food services or health care and social assistance. Not only are Black and Hispanic communities facing a disproportionate share of COVID-19 cases, but also they have the least ability to socially distance.

Conclusion

As COVID-19 cases continue to climb in Oregon and around the United States, people face an uncertain economic future. If Oregon follows the path of California, New York, or several other states, more aggressive social distancing efforts may be reinstated. Of course, public health policy is designed to save lives and has been incredibly successful in other countries. Nevertheless, opportunity costs exist and those costs are distributed disproportionately. It’s likely that industries like accommodation and food services or retail trade will be hit hard if those safety measures are necessary. We know that individuals who are Black or Hispanic, earn less, and have the least education have the worst access to remote work. For these sectors and workers, social distancing and telecommuting aren’t an option. As leaders design policy in response to COVID-19, it’s crucial that the 63 percent of workers who can’t work from home are protected.

Advertisement