Sale Prices Surge in Neighborhoods with New Tax Break

Sale prices ticked up sharply in some of the nation’s lowest-income and highest – poverty communities near the end of last year-but mostly in the neighborhoods now eligible for newly created tax breaks.

Tucked within the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) is a somewhat overlooked, but potentially massive, program: Opportunity Zones. Investors have flocked to these designated zones since last summer, when the Treasury Department certified the final batch of 8,700 census tracts selected by state governors.

Sweet deals for investors

The zones – a collection of low-income or high-poverty census tracts scattered across all 50 states and Washington, D.C. – offer potentially large tax savings for investors who fund projects in these communities. A laundry list of rules and regulations detail the precise qualifications for eligible investments, but the bottom line is that capital gains from other ventures that are funneled into Opportunity Zones eventually can be rewarded with up to a 15 percent discount on taxes they would have owed otherwise. And if that deal wasn’t sweet enough, investors who keep their money in the Opportunity Zone for at least 10 years avoid all capital gains taxes on profits from the Opportunity Zone investment.

The rationale behind the zones is relatively simple. Proponents argue that a lot of the wealth currently generated as capital gains could be put to good use as seed money in traditionally neglected communities shut out of investment – ideally revitalizing infrastructure, fueling economic growth, and spurring job creation and overall prosperity. But whether this tax break will direct funds to the communities that need them the most – or what happens when money arrives – are open questions.

Researchers contend that the particular tracts that were chosen as Opportunity Zones could determine whether the policy succeeds. Skeptics of Opportunity Zones argue a lax regulatory system and selection criteria can provide costly tax breaks for developments in areas already attractive to investors, essentially subsidizing projects that would have happened regardless of a tax break. Others fear the incentives may concentrate residential redevelopment in communities already vulnerable to gentrification and displacement, without many guardrails to mitigate undesirable outcomes.

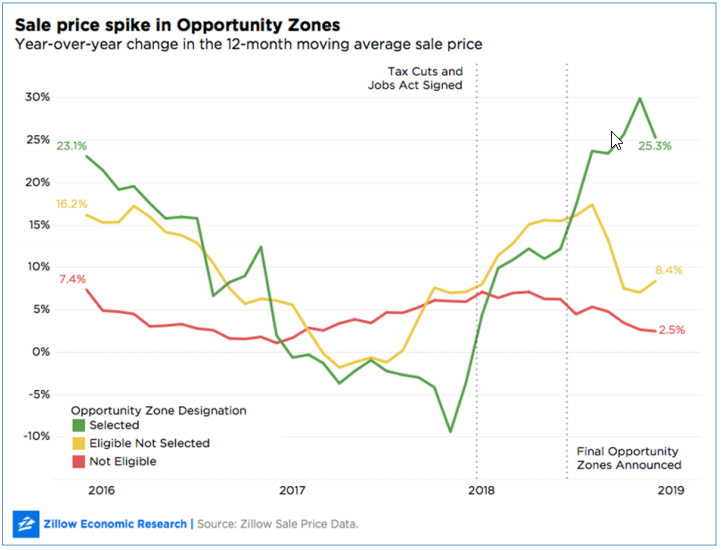

We are still in the program’s infancy, so these promises and fears are mostly theoretical. While it’s Southern Oregon Business Journal 17 still early, we already see some signals that folks have begun to take up Uncle Sam on his generous offer. Compared to similar tracts that were not selected, real estate sale prices are increasing at a faster rate in Opportunity Zones following their selection.

It appears the year-over-year change in sale prices for all eligible zones (selected or otherwise) were increasing months before the TCJA was passed, but the divergence after the final selection of Opportunity Zones provides an early signal of demand. In other words, the yellow and green lines moving upwards together in late 2018 may not have been solely due to TCJA and may indicate broader real estate trends in low-income areas. However, after the tracts composing the green line actually became Opportunity Zones, their sale prices took off. Similar analyses found surging sale values in land categorized as development sites within Opportunity Zones.

We calculated the 12-month moving average sale price in each month through the end of 2018 for each category, including all arm’s length transactions where sale price data were recorded.

We then calculated the year-over-year change in that moving average. Because real estate data are subject to seasonal variation, a 12-month moving average avoids putting too much weight on any one month that might have been subject to idiosyncratic shocks not related to market fundamentals.

Sales Prices in Opportunity Zones Grew by More Than 20% Year-Over-Year

For the most part, until selection of all Opportunity Zones, the selected tracts and the rejected tracts displayed generally similar price trends. During the period between the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the selection of Opportunity Zones, the year-over-year change in average sale prices grew between 10 and 15 percent in the Southern Oregon Business Journal 18 eligible tracts, regardless of whether they were ultimately chosen as Opportunity Zones. However, in the months immediately following the final selection of Opportunity Zones, the price trajectories diverged. Sale prices in eligible but not selected tracts began growing more slowly and by single digits, whereas sale prices in Opportunity Zones started growing by more than 20 percent year-over-year.

It’s crucial to note that Opportunity Zones are still very much in their infancy, and we are measuring very early signals of how the tax breaks may correspond to real estate trends. It remains to be seen whether this uptick in Opportunity Zones is a flash in the pan, or the start of something larger.

It’s also very likely that the big money hasn’t even started pouring into these zones yet, as many funds may watch from the sidelines until more rules and regulations are hammered out. If that’s the case, signals we see in transaction data now might be drowned out in the coming months if waves of new capital begin pouring in.

Finally, while changes in average sale prices provide one lens for viewing investment demand for certain types of property, they are an incomplete measure that will need to be expanded upon as we track this policy in the coming months.

Reprinted by permission: https://www.zillow.com/research/ prices-surge-opportunity-zones-23393/

Advertisement