Disparate Impact: COVID-19 Job Losses by Sector and Gender in Oregon

Every recession is unique, with varying impacts on workers in different parts of the economy. The dot com recession in 2001 hit high-tech harder than other sectors. Construction bore the hardest brunt of job losses during the Great Recession. The COVID-19 recession, now in its eighth month, is showing its own set of disparate impacts in Oregon and nationwide.

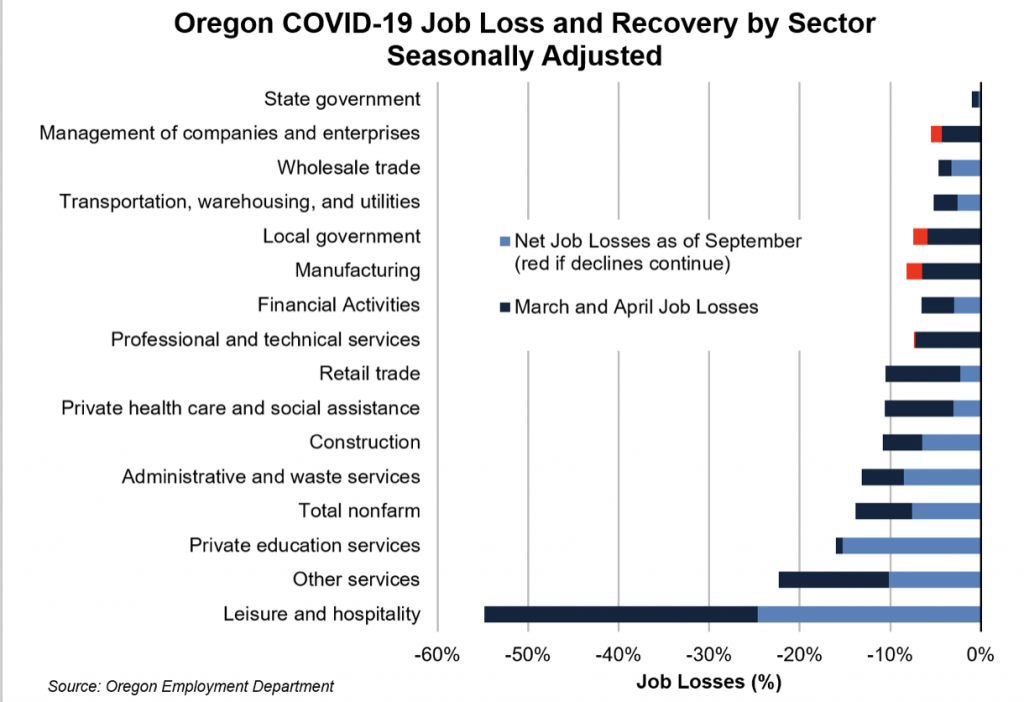

In March and April, Oregon’s total nonfarm payroll employment dropped by 271,900, or 13.8 percent. Oregon regained nearly half (45% or 122,100) of the net job loss between May and September. Both the initial spring losses and the rebound in employment looks quite different by sector and across workers of varying demographics.

Initial Shock by Sector

One out of every eight jobs in Oregon was either temporarily or permanently lost in two months’ time. That’s a stunning and unparalleled rate of job loss over such a short period. Three of the state’s service-based sectors lost even larger shares of jobs. Leisure and hospitality – including hotels, restaurants, and theaters – shed 118,700 jobs in March and April, more than half (-54.8%) of its employment. Other services – which includes automotive repair, barber shops and beauty salons, and parking garages – dropped one out of every five of its 65,800 jobs (-22.3%). Private education services also saw sharp declines (-6,000 or -16.0%) as schools shuttered in the spring.

Recovery is underway in each of these sectors. By September, leisure and hospitality and other services each regained more than half their spring job losses. Private education has been slower to rebound. These establishments have only added back 300 jobs, as instruction remains largely online and initial estimates show lower enrollments. Even with the initial bounce back, these combined sectors remain 73,600 jobs below their February level.

Second Wave of Job Losses

While most sectors are rebounding from the initial COVID-19 recession job losses, others are starting to see additional declines as COVID-19 and its economic impacts linger. The state’s corporate headquarters companies, local government, and manufacturing each had lower rates of job loss than Oregon overall in March and April.

They’re still on the downward slide though. From May to September, manufacturing lost another 3,400 jobs, for a total decline of 8.2 percent since February. Similarly, local government – roughly half of which is K-12 and higher education – dropped by 13,600 jobs (-5.9%) in spring, and lost another 3,600 jobs since then. The largely corporate management of companies sector initially lost 2,200 jobs (-4.3%), and lost another 600 since May, for a total drop of 5.5 percent.

Job Losses in Female-Dominated Sectors

The differing makeup of each sector’s workforce, and different impacts of the COVID-19 closures by sector, means workers in some demographic groups are feeling this recession to a greater degree than others so far. Women held the majority of jobs in each of the three sectors with the largest initial losses by share. In 2019, the Census Bureau’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators show women held two out of three jobs in private education services. They accounted for 54 percent of jobs in leisure and hospitality, and 55 percent in other services.

Women also hold two out of three jobs in public education services. Most public school districts in Oregon remain physically closed, and as detailed by the Office of Economic Analysis, that’s creating negative employment impacts. Enrollments are down, and online education largely cuts the need for substitute teachers.

Jobs in management of companies were evenly split between men and women in 2019. While manufacturing was and is male-dominated (72% of jobs), the total loss in the female-dominated private sectors listed above has been four times greater to date in this recession.

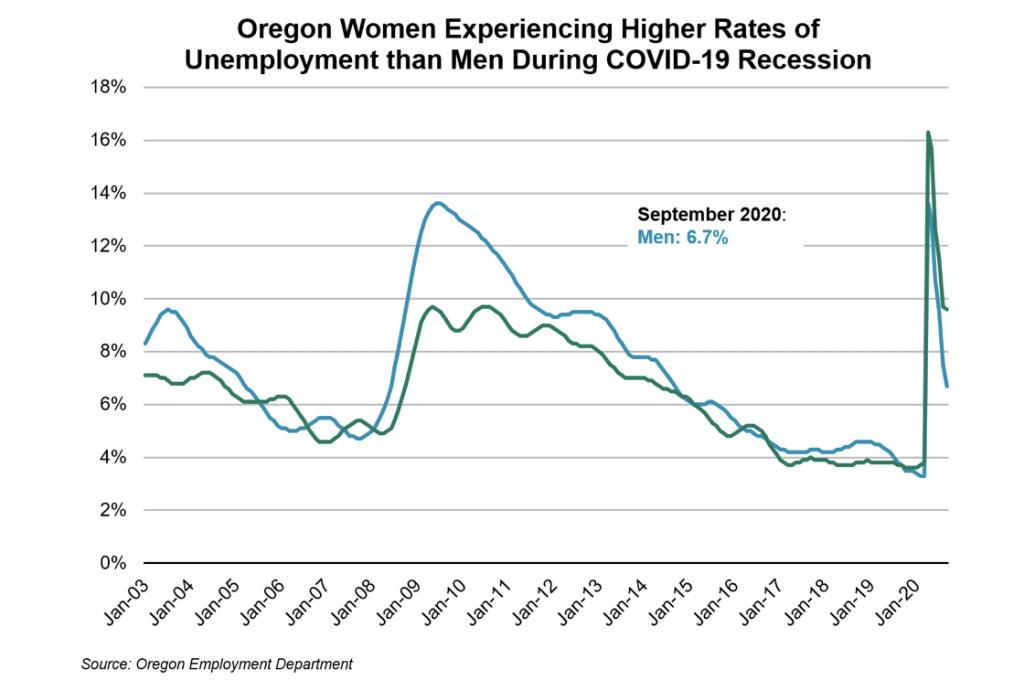

Women’s Unemployment and Labor Force Outcomes

The disparate impact to sectors where more women have jobs is reflected in unemployment rates. Since the COVID-19 recession began in Oregon, the unemployment rate for women has consistently been 2 to 3 percentage points higher than for men. In September 2020, the unemployment rate for women was 9.6 percent, compared with 6.7 percent for men.

Unemployment rates only capture those who’ve remained in the labor force. If someone lost or quit a job, and hasn’t actively looked for one in the past four weeks, or isn’t available or able to take a job offered to them, they’re no longer counted as being in the labor force.

In addition to higher unemployment rates, women have also exited the labor force in higher numbers than men. Nationally, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported women left the labor force at four times the rate of men in September 2020. Oregon has seen a similar trend to the nation, with significantly more women than men departing the labor force, particularly since the summer.

Working parents – and especially working mothers, who often shoulder more at-home care responsibilities and often earn less – are facing increased pressures of juggling child care, young children’s virtual learning, and their own jobs, many of which aren’t possible from home. With reduced child care options and continued social distancing, parents are facing these challenges without the usual supports from educational and social programs. A recent NPR article notes, “The pandemic’s female exodus has decidedly turned back the clock by at least a generation, with the share of women in the workforce down to levels not seen since 1988.” In addition, the national outflow of women in the labor force in September was particularly concentrated among Latinas. “As hundreds of thousands of women dropped out of the workforce in September, Latinas led the way, leaving at nearly three times the rate of white women and more than four times the rate of African Americans.”

Education: the Linchpin

The COVID-19 closures for health and safety measures have resulted in unparalleled job losses in majority-female sectors. With only partial recovery in these sectors, and the continued closure of many education services establishments, women have seen disproportionate, negative outcomes in unemployment and labor force departures. Other disparate impacts have occurred so far in this recession as well – by geography, and race and ethnicity – which will continue to be researched and published at QualityInfo.org in the coming weeks and months.

By Gail Krumenauer

Oregon State Employment Economist

gail.k.krumenauer@oregon.gov

Advertisement