6 Lessons We Can Learn from Frank Lloyd Wright

From blog – https://www.1000museums.com/six-lessons-frank-lloyd-wright/

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) was an icon of modern architecture. Over a period of 70 years he built more than 1,000 buildings across the United States, dotting the landscape with his elegant style. He designed organic exteriors of wood and stone as well as interior elements, including stained glass windows, furniture, tableware, and rugs.

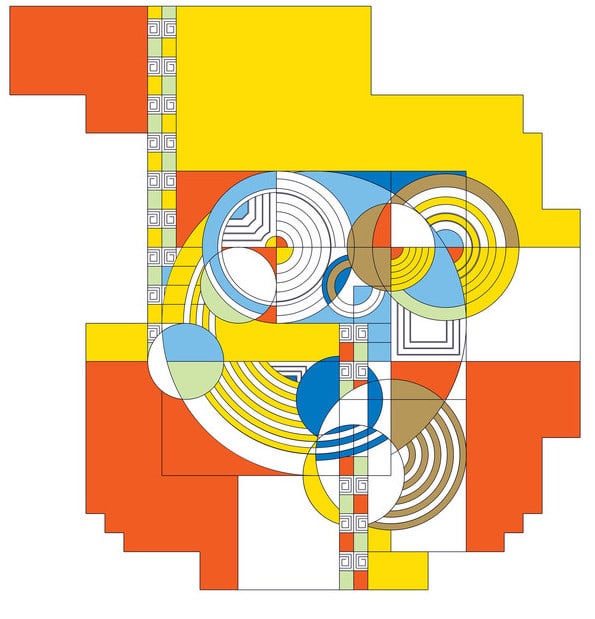

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hoffman Rug, 1955. From The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All rights reserved.

In his writings and in his work at his Taliesin Fellowship, Wright liked to share his philosophy of life, his thoughts on design, and his personal values, ensuring that his legacy is not just gorgeous buildings but also advice on how to live a life of meaning and beauty. In this article, we will look at six lessons that we can learn from the work of Frank Lloyd Wright.

1. Life Is Beautiful

Before Wright was born, his mother Anna said that she expected her first child to grow up to build beautiful buildings, according to Wright’s autobiography. She wasn’t wrong. Throughout his life, Wright built beautiful houses, museums, hotels, churches, synagogues, civic centers, and other buildings. Wright believed that the point of architecture was to share beauty. He said that, “The mission of an architect is to help people understand how to make life more beautiful, the world a better one for living in, and to give reason, rhyme, and meaning to life.”

He was born on June 8, 1867, in Wisconsin, where he spent most of his childhood, and studied engineering at the University of Wisconsin. After school, Wright moved to Chicago and worked for the firm of Alder & Sullivan. He opened his own successful practice in 1893 and established a studio in his Oak Park, Illinois home in 1898. One of his early commissions was to design a home for Austrian businessman Isidore H. Heller and his family who had recently bought a plot of land in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago. Wright built the house out of Indiana limestone and Roman brick.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Isidore Heller House, 1896. From the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All rights reserved.

The Isidore Heller house displays the influence of Louis Sullivan, Wright’s earlier employer and mentor. Sullivan is famous for his skyscrapers, and, although the Isidore Heller house isn’t a skyscraper, its height, arcaded balconies, and intricate friezes show a Sullivan influence. Later, Wright would simplify his designs and do away with ornamentation and fanciful elements. The Heller house represents the beginning of a new aesthetic with its clean, horizontal lines and elegant design.

Product 1FRANK LLOYD WRIGHTHoffman Rug$16-$489BUY NOWProduct 2FRANK LLOYD WRIGHTDr. Toufic H. Kalil House Illustration$16-$489BUY NOWProduct 3FRANK LLOYD WRIGHTTree of Life Window$16-$489BUY NOW

2. Housing Should Be Affordable

When we think of Frank Lloyd Wright these days, we don’t think about affordability, but Wright strongly believed that everyone should be able to afford a house. He designed houses for ordinary people through the careful use of standardization and the sourcing of inexpensive materials. During the Great Depression, he realized the need for affordable housing and developed his signature Usonian house design. He coined the term “Usonia” from the term “US” to describe an architectural design for the middle class in the United States. The houses were constructed of modular concrete blocks and were economical while still looking sophisticated. The building plans were streamlined, with a simplistic approach to the construction, proving that beauty could be affordable.

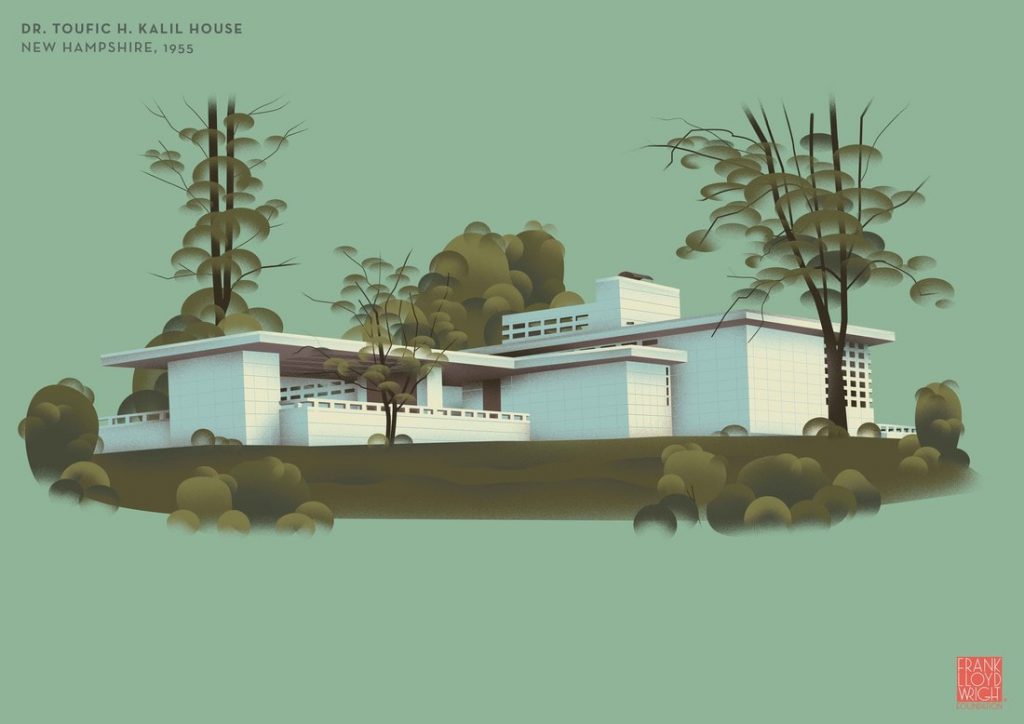

Frank Lloyd Wright (Building), Dr. Toufic H. Kalil House Illustration. ® /™ /© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Wright built the Dr. Toufic H. Kalil House in Manchester, New Hampshire in 1955 for Dr. Toufic and Mildred Kalil, a professional couple. It is an iconic example of Usonian architecture. Typical of the style, the Kalil house draws its beauty from simple, linear lines rather than ornamental details. Symmetrical rows of rectangular windows provide a lighter complement to the heavy concrete of the walls, and the house fits organically into its wooden site, as was typical of Wright houses.

The 1,380-square-foot house contains a living room, kitchen, two bedrooms, two baths, and a study. All of the original furniture, most of which is built-in, is still intact. In September 2019, the house was put up for sale with an asking price of $850,000. The Currier Museum of Art, also in Manchester, purchased the house and recently opened it for public tours.

The illustration of the house shown above is part of a series of illustrations created by HomeAdvisor, a digital marketplace for home improvement projects famous for their Angie’s List. HomeAdvisor explained their inspiration for the illustration project in this 2020 article where they also explored their process for selecting which houses to illustrate. The Frank Lloyd Foundation worked with 1000Museums to ensure that prints of the illustrations are available for purchase, with proceeds supporting the Foundation. To see the full collection of illustrations, navigate to the 1000Museums Focus on Frank Lloyd Wright page here.

3. Craftsmanship Matters

Wright was influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, an international theory of design that focused on craftsmanship. Wright’s vision shared with the Arts and Crafts movement an embrace of skilled handcrafting as an antidote to the dehumanizing effects of modern mass production. Wright said, “I believe a house is more a home by being a work of art” but he also recognized that homes need to be well-built.

The Arts and Crafts movement influenced the Prairie School, a group of Chicago architects led by Sullivan and Wright who designed houses to evoke the low, earth-toned landscapes of the North American prairies. Prairie School architecture rejected the ornate fussiness of English-inspired Victorian styles and sought to define a uniquely North American style.

The craftsmanship of the Prairie School houses needed to be solid to withstand the harsh winters and hot summers of the American Midwest. The houses had low-pitched roofs and wide overhanging eaves. The exteriors featured long horizontal lines, windows grouped in horizontal bands, and very little ornamentation. The interiors were often more ornate, but still used elegant and simple designs. The style fits Frank Lloyd Wright’s belief that life should be beautiful while also being practical.

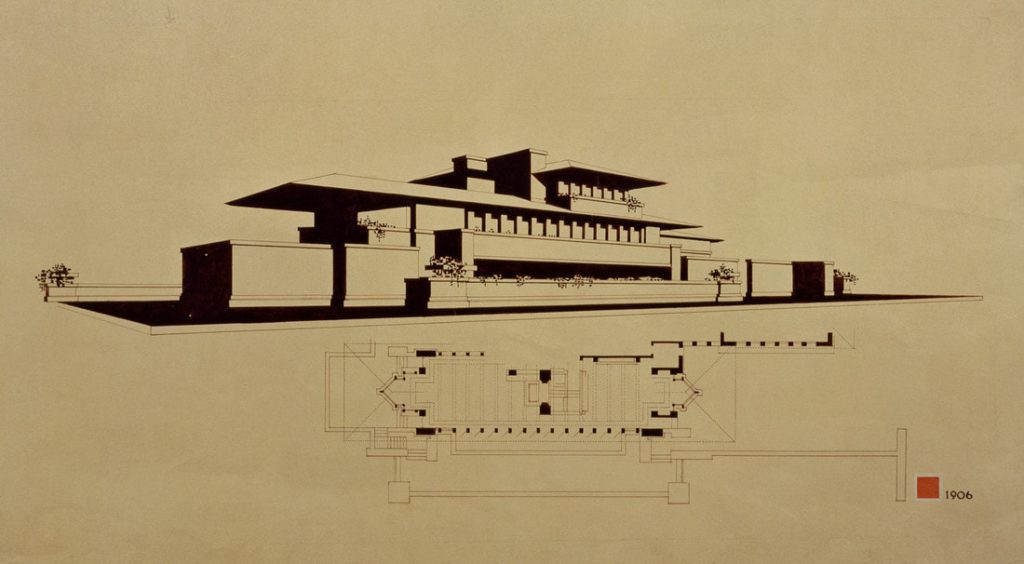

Frank Lloyd Wright, Frederick Robie House, 1908-1910. From The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All rights reserved.

The Frederick C. Robie House is an iconic example of the Prairie School. Wright designed the house as well as all of the interiors, windows, lighting, rugs, furniture, and textiles. The house is now on the campus of the University of Chicago in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, but when it was built between 1908 and 1910, the lots around it were mostly vacant. It was designed as a single-family home for the Robie family who wanted to be close to the social life of the university where Mrs. Robie had recently graduated.

4. Architecture Should Be Eco-Friendly

It would be exaggerating to say that Wright understood eco-friendly design and sustainability in the same way that today’s architects do, but Wright cared deeply about the environment and the importance of using materials wisely. He worked with natural materials and built his homes to integrate with nature. He preferred to leave natural materials, such as wood and stone, plain, unpainted, and not plastered over, and he loved to have lots of open spaces in his interiors with many windows to merge the inside and outside. He designed his houses to appear as if they grew from their site, shaped by the landscape and colored by the nearby fields or forests, and as beautiful and functional as nature.

"No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other."

– Frank Lloyd Wright

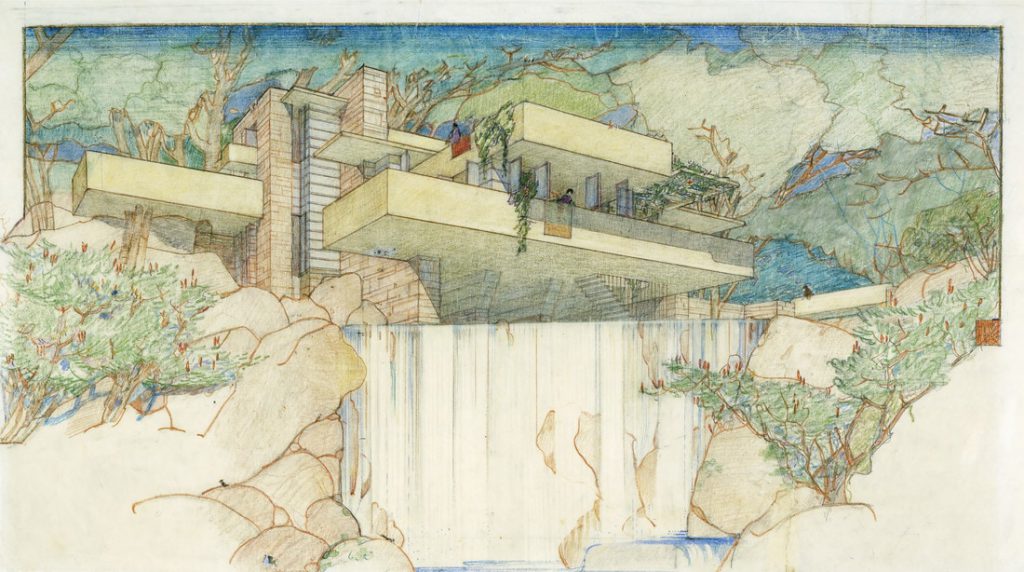

Wright believed buildings should exist in harmony with the humans that use them and with their natural surroundings, a philosophy he called organic architecture. Houses such as his well-known Fallingwater in rural southwestern Pennsylvania blend into their natural surroundings, both drawing inspiration from and contributing to the setting.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Edgar J. Kaufmann House, “Fallingwater”, 1935. From The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All rights reserved.

Fallingwater is located in the Laurel Highlands of the Allegheny Mountains. It was built partly over a waterfall on the Bear Run tributary of the Youghiogheny River in the Mill Run area of Fayette County, Pennsylvania. The house was designed as a weekend home for the family of Liliane Kaufmann and her husband, Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr., owner of Kaufmann’s Department Store. Fallingwater stands as one of Wright’s greatest masterpieces, both for its dramatic presentation and for its integration with its stunning natural surroundings.

5. Celebrate Individuality

No two Frank Lloyd Wright houses are the same. Each house has an individual style designed to fit the personality of the client who requested the house. Wright said that there should be as many styles of houses as there are kinds of people, and as many differentiations as there are different individuals. Even his Usonian houses, which used standardized designs, supported many options for clients to customize them.

Wright himself valued his own individualism, sometimes to a fault. Unlike many architects, he didn’t join the American Institute of Architects, and in fact called the organization “a harbor of refuge for the incompetent” and “a form of refined gangsterism.” He rarely credited any influences on his designs, though clearly he was influenced by his early employer Louis Sullivan.

He also didn’t give his protégés credit for their work. For example, Marion Mahony Griffin, one of the Prairie School architects, drew many renderings of Wright’s houses and was rarely credited, although Wright did praise her rendering of the K. C. DeRhodes House in South Bend, Indiana, according to author Lynn Becker. Griffin’s diagram of the house is no longer available, however, an illustration of the house is part of the HomeAdvisor collection of illustrations.

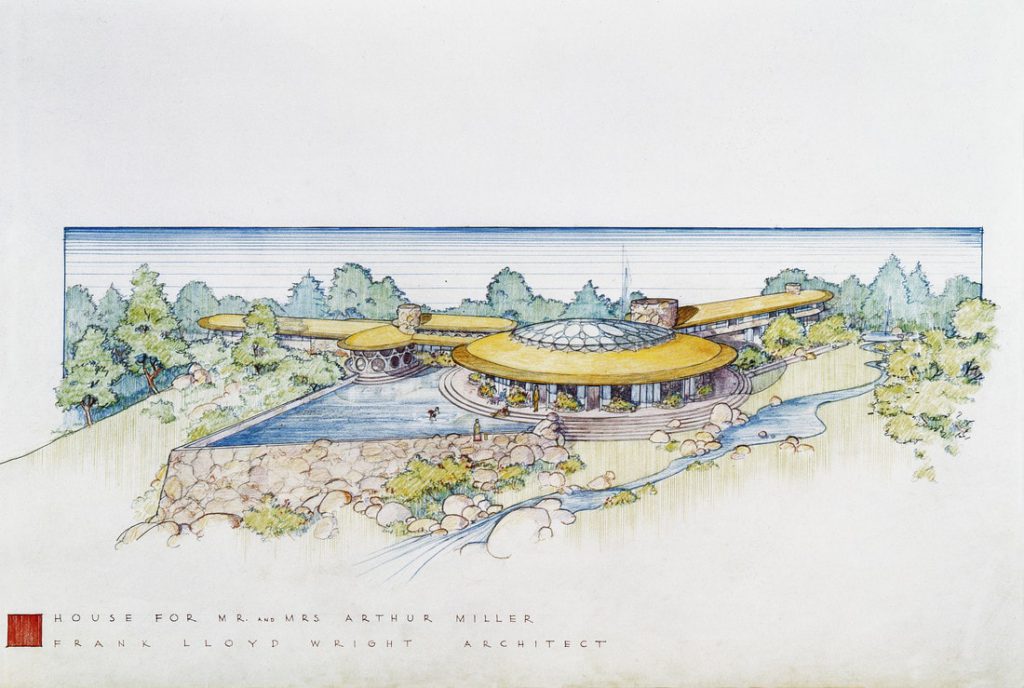

Wright believed in individualism and individuality. His belief in individuality carried over into his architecture designs, where every design was unique. This can easily be seen in the house that he designed for the author Arthur Miller and his wife, actress Marilyn Monroe.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe House, 1958. From The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All rights reserved.

The Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe House was never built, although the King Kamehameha Golf Course Clubhouse in Waikapu, Maui, Hawaii is based on the design. The marriage between Miller and Monroe, two very different personalities, did not last long enough for the house to be built. It was mainly Monroe who worked with Wright on the design for the Connecticut home, but unfortunately, her ideas were not a good fit for her more serious husband. The design features a dramatic circular living room, covered with a domed ceiling and skylights and surrounded by columns, and a swimming pool that would have been built into the side of a hill with natural stone walls. The design is a case where Wright understood the individuality of one of the clients, but alas not his other client, her husband.

6. Finish What You Start

Although quite a few of Wright’s designs were never built, more than 1,000 were, and Wright believed that once started, the architect should stick with the work. Wright considered the architect’s job to be more than just the exterior design. The planning for a house isn’t finished until every detail is attended to, whether it’s the windows, furniture, rugs, fabrics, lighting, or tableware. He wrote, “In organic architecture then, it is quite impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and its setting and environment still another.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, Tree of Life Window, 1904. Art Glass Design, ©2014 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Wright’s life was marred by major mistakes and tragedy, a sad complement to a life otherwise defined by beauty. He abandoned his first wife and had a tempestuous marriage with his second wife who was a morphine addict. After separating from his first wife, he lived with his romantic partner Mamah Cheney who was murdered by a disgruntled worker at Taliesin, the home and studio that Wright had built in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Wright was working in Chicago when the worker set fire to the living quarters at Taliesin and then killed seven people with an axe as the fire burned. The dead included Cheney and her two children.

Wright turned the problems he experienced as a younger man into a life of hard work, teaching, and creating art. He and his third wife, Olga Ivanovna, founded the Taliesin Fellowship in Wisconsin, with a winter camp at Taliesin West in Arizona, where they taught architecture and construction. The classes included lessons in gardening, cooking, music, dance, and philosophy. He instilled a work ethic and artistic aesthetic in his apprentices and made sure they understood that “all fine architectural values are human values, else not valuable.” Wright passed away in 1959 after a long tumultuous life, leaving a legacy of innovation and many lessons about life and art.

"The longer I live, the more beautiful life becomes." – Frank Lloyd Wright

Here at 1000Museums, we can’t sell you a beautiful Frank Lloyd Wright house, obviously, but we can sell you a beautiful archival reproduction of an architectural drawing or a print based on one of Wright’s other objects, such as a rug or stained glass window. We invite you to shop the collection here!

Advertisement